Silence

Words of Spirituality

by ENZO BIANCHI

The spiritual and ascetic tradition has always seen silence as essential to an authentic spiritual and prayer life

The spiritual and ascetic tradition has always seen silence as essential to an authentic spiritual and prayer life. "The father of prayer is silence, the mother of prayer is solitude," Girolamo Savonarola said. Silence alone makes listening possible - in other words, it alone allows us to welcome within us not only the Word, but also the presence of the One who speaks. Through silence we awaken to the experience of the indwelling of God, because the God we seek by following the risen Christ in faith is a God who is not outside of us, but who dwells within us. In the fourth Gospel Jesus says, "Whoever loves me will keep my word, and my Father will love him, and we will come to him and make our dwelling with him" (John 14:23). Silence is a language of love, of depth, of being present to another. In the experience of love, it is a language that is often much more eloquent, intense and communicative than a word.Today, unfortunately, silence is rare. It is what most is missing in a world in which we are deafened by noise, bombarded by visual and auditory messages, and bereft of - at times almost exiled from - our interiority. It is not surprising, then, that "when the prestige of language diminishes, that of silence increases" (Susan Sontag). Spiritual life as well shows signs of a lack of silence: today's liturgies are often heavily verbal, weighed down by texts that, by seeking to explain all and say all, forget that in God there is a dimension of wordlessness, silence and mystery that the liturgy should reflect.

The growing demand for authentic spiritual life is too often neglected by local churches that are involved instead in countless social, charitable, recreational, and catechetical activities. Given this situation, the widespread interest today in forms of spirituality that are not Christian should not surprise us. We need to recognize our need for silence! We need silence from a purely anthropological point of view, because we are social beings, and only a harmonious relationship between words and silence makes our communication well-balanced and significant. From a spiritual point of view as well, though, we need silence. In Christianity, silence is a dimension of our humanity, but also a theological dimension. Alone on Mount Horeb, the prophet Elijah hears first a strong wind, followed by an earthquake and then a fire, and finally "the voice of a fading silence" (1 Kings 19:12). When he hears this, Elijah hides his face in his cloak and steps into the presence of God. God reveals his presence to Elijah in a silence that is eloquent, and elsewhere in the Bible the revelation of God is communicated not only with words, but also in silence. For Ignatius of Antioch, Christ is "the Word that proceeds from silence." The God who reveals himself in silence and through the Word asks human beings to listen, and in order to listen we need silence.

Of course, refraining from speaking is not enough - we also need interior silence, that dimension that restores us to ourselves and places us on the level of being, face to face with what is essential. "Inherent in silence is a marvelous power of observation, clarification, and concentration on the things that are essential" (Dietrich Bonhoeffer). It is from silence that an acute, penetrating, judicious and luminous word can arise, a word that we might also call therapeutic, capable of offering consolation. Silence is the guardian of interiority. Yes, we are speaking about a silence that can be defined in negative terms as moderation and discipline in speaking, or even as abstention from speaking, but from here we move toward an interior dimension in which we also silence the thoughts, images, protests, judgments, and complaints that arise in the heart: "from within people, from their hearts, come evil thoughts" (Mark 7:21). This is the difficult interior silence that must be sought and pursued within the heart, the site of the spiritual struggle. Yet it is this profound silence that generates love, empathy, attentiveness toward others, and the ability to welcome them. Silence creates a space deep within us so that in it the Other can dwell and his Word remain. In this space, love for the Lord is rooted deeply in us. At the same time, interior silence makes us capable of listening intelligently, speaking with discretion, and discerning what burns in the heart of another, concealed in the silence from which his or her words arise.

Silence, this silence, becomes the source of our love for others. This is why the double commandment of love for God and for our neighbor can be fulfilled by those who know how to be silent. Basil says, "A silent person becomes a source of grace for those who listen." At this point we can recall, without the risk of cliché, the words of E. Rostand: "Silence is the most perfect song, the highest prayer." If our silence leads us to listen to God and love others with genuine love - if, in other words, it leads us to life in Christ, and not to a generic and sterile inner void - then it is an authentically Christian form of prayer and pleases God. This interior silence has a long spiritual history. It is the silence practiced by hesychasts in their search for unification of the heart; it is the silence of the monastic tradition, a silence that allows those who practice it to welcome within themselves the Word of God; it is the silence of the prayer of adoration of God’s presence; it is the silence treasured by mystics of every religious tradition. Even more fundamentally, it is the silence that saturates poetic language, the silence that is the substance of music, the silence that is essential to every act of communication. Silence, an event of depth and unification, makes the body eloquent by guiding us to the habitare secum so highly valued by the monastic tradition, in which we learn to inhabit our body and our inner life. Inhabited by silence, the body becomes a revelation of the person.

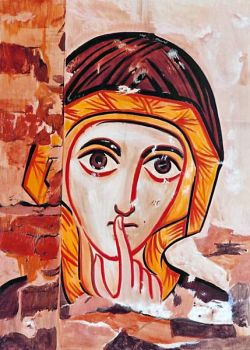

In Christianity we contemplate Jesus Christ as the Word made flesh, but also as the Silence of God. The Gospels show us a Jesus who, as he goes toward the passion, increasingly refrains from speaking and enters into silence, like a mute lamb. One who knows the truth and the inexpressible ground of reality neither wants nor is able to betray the ineffable in speech, but protects it with his silence. Jesus, who "opens not his mouth" (Isaiah 53:7), reveals that silence is what is truly strong. He makes his silence an action, and by doing so he is also able to make his death an act, the gesture of a living person. In this context it should be clear that behind both words and silence, what truly saves is the love that gives life to both. Who is the crucified Christ if not the icon of silence, the silence of God himself? The Gospels tell us that from noon until three o'clock in the afternoon, the hour of Christ's death on the cross, darkness and silence reign. All words about God, images, conceptualizations, and ideas about God are silent. It is against this silence that we should measure theology, every discussion about God, and every representation of God, because we always face the temptation to reduce God to an idol, a manufactured object that can be manipulated. The silence of the moment of the cross is able to express the inexpressible: the image of the invisible God is found in a man nailed to a cross. The silence of the cross is the authoritative source from which every theological word should be drawn.

From: ENZO BIANCHI, Words of Spirituality,

Society for Promoting Christian Knowledge, London 2002